Jean-Marie Mayeur and Madeleine Reberioux, The Third Republic from its Origins to the Great War, 1871-1914

The Two Frances

Demonstrations and organizations

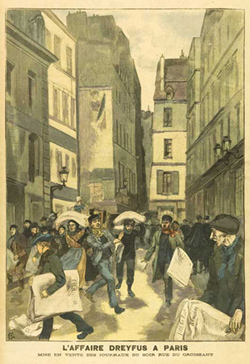

The violence of the passions unleashed by the [Dreyfus] Affair in France surprised the world. It is true that the press sometimes exaggerated these passions; for example,  police reports indicate that the day after Dreyfus's second conviction no surge of savage anger followed the very lively reactions of the newspapers. Yet the behaviour of the press was itself one of the factors in the bitterness of the confrontations; for months the Affair occupied the number-one position in numerous papers and banner headlines multiplied, following the example of Le Matin, which at the start was strongly anti-Dreyfusard, or of La Petite Republique, in which [socialist leader Jean] Jaures published 'the proofs' in August-September 1898. In the streets the agitation was at first and for a long time organized by the anti-Dreyfusards. They had in their favour numbers, passion, and a model in the events in Algiers, where colonial anti-semitism joined a growing autonomist feeling to unleash in the second fortnight of January 1898 what Ch. R. Ageron called 'a near-revolution' (Biblio. no. 211, vol. I, book 3). In Marseille, where Jews were numerous, the demonstrations which followed [Emile Zola's article] 'J'accuse' were accompanied by attacks on their shops. The larger the population of a provincial town, the earlier and longer-lasting were the demonstrations.

police reports indicate that the day after Dreyfus's second conviction no surge of savage anger followed the very lively reactions of the newspapers. Yet the behaviour of the press was itself one of the factors in the bitterness of the confrontations; for months the Affair occupied the number-one position in numerous papers and banner headlines multiplied, following the example of Le Matin, which at the start was strongly anti-Dreyfusard, or of La Petite Republique, in which [socialist leader Jean] Jaures published 'the proofs' in August-September 1898. In the streets the agitation was at first and for a long time organized by the anti-Dreyfusards. They had in their favour numbers, passion, and a model in the events in Algiers, where colonial anti-semitism joined a growing autonomist feeling to unleash in the second fortnight of January 1898 what Ch. R. Ageron called 'a near-revolution' (Biblio. no. 211, vol. I, book 3). In Marseille, where Jews were numerous, the demonstrations which followed [Emile Zola's article] 'J'accuse' were accompanied by attacks on their shops. The larger the population of a provincial town, the earlier and longer-lasting were the demonstrations.

As for the meetings, they were organized by both sides, especially in Paris where there were plenty of rooms capable of holding audiences of between 4,000 and 10,000. There was the Salle Cheynes at the rond-point de Ia Villette, the Saint-Paul riding-school in the heart of old Paris, the Guyanet riding-school in the avenue de la Grande Armee, where the anti-Dreyfusards gathered after the suicide of Henry, and the Tivoli Vauxhall, the fortress of Dreyfusism. The police occupied the approaches to these halls early on the evenings of meetings and their violence was proverbial. New social strata, mixing with the workers and students, thus had their first experience of a workers' meeting.

In the university cities - Bordeaux, Aix, Lyon, Rennes, Nancy - the students were in an awkward position; their social origin often gained them a certain indulgence from the police. Most of the Latin quarter remained on the right and people booed Dreyfusard professors in the street. But the response was not long in coming. In homage to Peguy, Daniel Halevy has left a memorable description of those times: 'A voice would shout, "Durkheim [one of the founders of modern sociology who was Jewish] is under attack! Seignobos has been overcome!" "Fall in!" replied Peguy, who always liked military expressions. Everyone sprang to attention and marched with him to the Sorbonne' (D. Halevy, Biblio. no. 21). Songs clashed everywhere; the Ça ira and the Internationale, the vocal weapons of the Dreyfusards, were countered by the nationalist hymn built on a pun in honour of Déroulède [a prominent rightist].

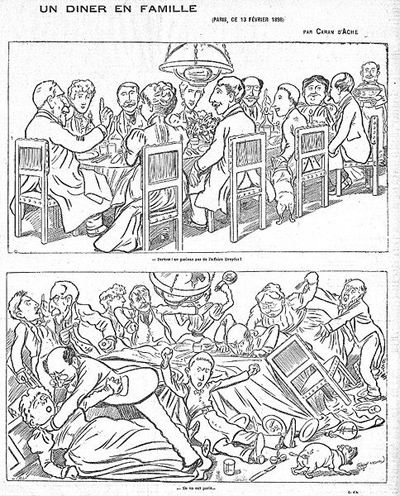

Even families were divided. It is hardly necessary to recall the drawing, the most famous of them all, by Caran d'Ache which appeared in Le Figaro on 13 February 1898. The drawing, entitled 'A family dinner', showed ten comfortable bourgeois at table. 'Above all, don't talk about the Dreyfus affair', says the master of the house as a servant brings in the soup tureen. A bit later table and chairs go over and the diners start fighting. 'They did talk about it.'

Just individuals to start with, Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards soon organized themselves. New structures arose in French society and others, old ones, were reactivated. The time of the leagues had arrived. One of the very first was the League for the Defence of the Rights of Man, conceived by the senator, Ludovic Trarieux, a former Minister of Justice, in February 1898, in the middle of the Zola trial. Its first general meeting took place on 4 June and its manifesto was published a month later. Taking its cue from its somewhat muted origins and the personality of its founder, a politically very moderate republican who did not mean to go further than the defence of the Rights of Man defined in 1789, the League equipped itself with a central committee on which sat respected intellectuals, and a few poli ticians chosen for their moderation- the old radical Ranc was the furthest to the left. It refrained from taking any political initiative. It is true that circumstances pushed it into action and prevented it from resting content with the study of individual cases. It collected large sums- 168,000 francs in a year - to publicize the truth about the Affair, its local sections organized numerous meetings and above all it provided chairmen and a deposit for public meetings. But its recruitment remained limited; at the end of 1898 it had 4,580 members and a year later 8,580. The League acquired a mass audience, but it was not a mass movement; it was more of a reception committee and working party. On the other side the League of Patriots was reborn, a Gambettist organization at the time of its foundation in 1882 and blessed at that time by Hugo and ... Joseph Reinach. Déroulède and his faithful lieutenant Marcel Habert put it back on the rails in September 1898. The times were different and so were the rails; it was no longer a question of grouping together all republican patriots but of organizing, in face of the parliamentary, semi-Dreyfusard Republic, a regime of 'mandarins and thugs', the supporters of the army and of a plebiscitary regime. A sister organization appeared on the scene, possibly a rival. This was La Ligue de la Patrie Française. It completed its organization in January 1899, just when the government was beginning to turn timidly towards revision; the movements of the government pendulum were matched at one moment by the defence, if need be against the government, of the 'Rights of Man' and at the next by that of the 'Patrie'. Jules Lemaitre, a fashionable literary critic, and François Copée, a popular poet and dramatist, held the new league over the baptismal font. [Maurice] Barrès [an influential French nationalist] joined its committee. Short on dogma and aiming to make itself a mass movement, it avoided appealing, like Deroulede, to the 'sacred bayonets of France' and after two months was able to announce that it had some 100,000 members. The League of Patriots was to be almost a religious order; the Ligue de la Patrie Française was a movement which was inflated by the wind of opinion and was to collapse again almost as quickly. And finally there was the Anti-semitic League, the bastion of the extreme anti-republican right, founded in 1890 by Drumont and run since 1896 by a fairly shady character, Jules Guerin.